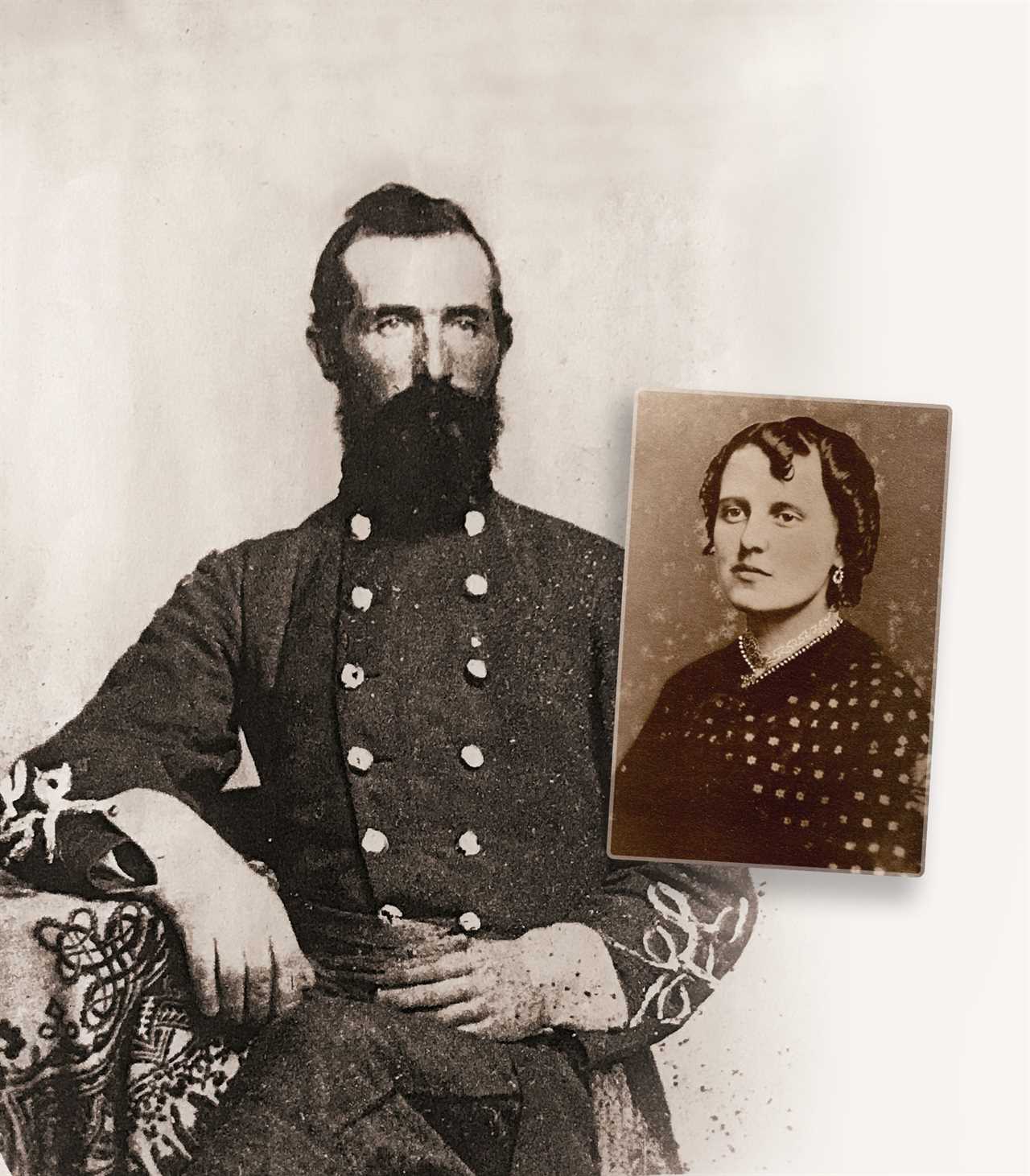

William C. “Jack” Davis

(Courtesy of UNC Press)

Civil War historian William C. “Jack” Davis, retired professor of American History at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, recently collaborated with Sue Bell on a project to edit letters dating from 1863 to 1865 between Sue Bell’s great-great-grandparents: Anne “Nannie” Radford Wharton, 19, who had just wed Gabriel “Gabe” Wharton, a 37-year-old officer in the Confederate Army. Wharton would serve under Generals John Floyd, John Jones, Jubal Early, and John Echols, primarily in southwestern Virginia. The recently discovered letters, long stashed in descendants’ attics, are now published in The Whartons’ War (UNC Press, 2022). They allow an intimate look at the home front during the last two years of the war, as well as an astoundingly candid glimpse into the personal lives of two privileged Southerners coming to grips with the dissolution of the world they have known.

How did you come across the extraordinary cache of letters?

About 50 years ago, I wrote a book about the Battle of New Market, Va., and I tracked descendants of almost all the commanders involved to see if there were any personal papers. I tracked down William Wharton, grandson of Gabriel Wharton, but he didn’t know of any. At that moment, two floors above him, were 15 boxes and a couple of steamer trunks full of General Wharton’s papers. The Wharton family sold the home in 1988, and the small industrial firm that bought it donated the house to the city of Radford [Va.] as a museum and gallery. They discovered the collection in the attic, and it was moved to a garage in Florida. Then Sue Bell, General Wharton’s great-great-granddaughter, brought them all to her home in Amherst, Mass. Among the items was the volume of 524 letters stitched together, letters between Wharton and his wife, and thousands of documents. One of the very unusual things about this collection is that Nannie’s letters survived. Typically, the woman’s letters—wife, mother, whomever—didn’t survive because they got carried around in a soldier’s knapsack, got wet, or were read or reread until they fell apart. But General Wharton kept her letters, and every few months he would send them all back to her, and he told her to put them all together into a book to preserve them.

Another great thing about the collection is that it opens the door on southwestern Virginia itself—on what was going on in one of those overlooked backwaters that was, in fact, vitally important to the Confederacy, in part because it was home to the only east-west railroad, and it was a major source of lead, coal, and other such essentials. There’s a great deal from both Gabe and Nannie about what the Civil War was like here in the region.

Nannie and Gabe write and receive letters so frequently. How was that possible?

The Confederacy had a post office department, the only one in our history that actually made a profit. With secession, John Reagan was appointed postmaster general of the Confederacy and contacted every Southerner working for the post office at the time and offered them a job. He told them if you take the job and come south, go to the stock room in your office first and stock up on letterhead, paper pencils, everything else. So, Reagan kind of stole the post office—the route maps and everything else.

It is surprising how quickly the Whartons received their letters. She’s in Radford, and most of the war he was within 200 miles, especially when he was in the Shenandoah Valley. There are couriers, coaches, and trains going up and down the Valley every day. It took only 2-3 days for her to receive a letter from him.

Did you find what you hoped for in these letters?

I was hoping for information about New Market, and there was in fact one full letter in good detail that wasn’t otherwise available. I really didn’t know what to expect otherwise because I didn’t know much about Wharton’s personality. Both he and his wife are very well-educated people. Responsible, very aware of what is going on in public events, and what I was hoping to find—and did—was an inner window on the dynamics of a high-ranking officer’s marriage during all the pressures of the war. We have a lot of material on the enlisted ranks and some from the general officer ranks, but not that much.

What I did not expect was to find that they are really in their way 21st-century people. They are kind of out of their time in their attitudes. Nannie is shrewd; she is a tough customer in business and she’s very, very direct, which is not the role that society expected of an upper middle-class woman in that era. Whereas General Wharton is all about feeling. It’s like someone today who at the drop of a hat will start gushing about how he’s feeling. I’m not saying he’s not manly. He doesn’t seem hung up in the male ethic of the time. He’s willing to be very sensitive and vulnerable, and his openness with her is pretty striking. There’s one letter in which he says he really didn’t care that, if she preferred, he would take her last name when they got married.

Wharton frequently criticized his superiors. Was there no fear of his letters being disclosed?

That’s not really uncommon in lower-level general officers’ correspondence to people whom they trust. If they dislike or resent a senior officer, they’re usually not hesitant to say so, or if they are critical of the way the war is being conducted. Both Gabe and Nannie are highly critical of the way the war is being carried out. She doesn’t think much of Robert E. Lee; neither one of them has a good word to say about Jefferson Davis. Something else that surprised me was to see how conditional their sense of obligation or loyalty was to the Confederacy. The war was really getting in the way of their love affair, and they both talked about being willing to pick up stakes and leave it all behind.

The Whartons’ letters offer a unique glimpse of wartime conditions in their hometown of Radford, Va. Pictured here is the Radford home that Gabe built for Nannie in 1875, which now serves as a museum and gallery.

(Courtesy of Glencoe Mansion, Museum and Gallery, Radford Heritage Foundation)

I was surprised to see that Gabe offered to let Tim, the husband of a couple owned by Nannie and who was working for Gabe in the war, seek freedom, if he would do it in a certain way.

He wanted him to step forward manfully and tell him what he wanted to do. He’s offering him money and a horse to help him out. I have never run across that anywhere before. The dynamic between the Whartons and Tim and Emeline Lewis is really interesting. There’s no question that the Whartons regard Tim and Emeline as property, as people did in that time and place. They were interested in their romance and lives—somewhat like talking about the romance between children—but they seemed to be very seriously interested in their welfare. Nannie blows up at Emeline pretty frequently, but Tim and Emeline stay with them for some years after the war as employees on their farm, which is not unusual.

Nannie and Gabe kept diaries. Will their diaries ever be available?

Wharton’s Civil War–era diaries are somewhat sparse. Unfortunately, he loaned his diary for 1864 and never got it back, so it is lost. There’s a lot of other papers relating to Wharton’s command, official papers, rosters, orders and that sort of thing, and a lot of correspondence with Confederate generals. One of the most interesting times I’ve ever had was several years ago when Sue Bell and I first met. I was in Washington, and when we met she handed me an envelope she had never opened. She was waiting to let me open it. It was pretty fat, and on the outside was written the words General’s Letters. The first thing on top was a completely unknown four-page letter by John C. Breckinridge; there was a letter by Robert E. Lee, Jubal Early, Stephen Ramseur, all sorts of people, during the war that no one ever knew existed.

There’s a lot of material there that’s not in the letters, a lot of prewar material. Wharton was involved in surveying the potential overland route for a wagon road down through the Gadsden Purchase and on to California, which might have become a Southern Transcontinental railroad but didn’t. All of his diaries from then survived, and his later diaries when he was a land agent in Arizona. It’s about 15 boxes and a couple of steamer trunks. He saved everything. There are two or three toothbrushes; the shirt he wore at his son’s wedding; some of Nannie’s clothing, souvenirs—a dried up rock-hard piece of a biscuit that Nannie baked for him that he kept as a souvenir after she died.

This article first appeared in America’s Civil War magazine

See more stories

SubscriBE NOW!

Facebook @AmericasCivilWar | Twitter @ACWMag

General Wharton had so much sentimentality. What was his skill set?

He was clearly very intelligent. One of the biggest challenges in editing the correspondence of these two was tracking down the obscure quotations they keep throwing into their letters. They were very well read and expressed themselves very well. He graduated 2nd in his class at VMI, a top-notch engineer. Very competent at all the skill sets required of a man of that era. What he didn’t have, and it relates to this sentimentality that is such a motivation in his personality, was the ability to be stern or tough with people, to say no. After the war, they experience almost constant monetary problems because he’s made loans to people who won’t pay him back and he won’t take them to court. It’s a big bone of contention between them. Nannie wanted to collect and goes about trying to do it herself. She even confronted a fellow with a pistol in Radford. She’s not afraid of anything.

One thing Nannie’s clearly is afraid of is childbirth. Was that fear common? Was it due to her small size?

Some of her clothing survived, and I doubt a 20-year-old woman today could get into it. She couldn’t have weighed more than 85 pounds. Her waist was 14-15 inches, something like that. Plus, in her family and among her set of friends there were several instances of women dying in childbirth.

She seemed even to instruct him on when not to have sex with her.

There’s a remark in one of his letters, after her first false alarm regarding pregnancy has passed. He says something to the effect that I shall be sure never to place you in that danger again. At the same time, unusual for that era, there’s a code between them. They kind of hint at marital pleasures. He reminds her of room 41, where they stayed in Atlanta, on the anniversary of their honeymoon. It’s always dangerous for historians to put someone 150 years ago on the couch, but just based on people I’ve known, who’ve exhibited that kind of behavior, I wonder if Nannie wasn’t bipolar. She may just have been quick-tempered. She had peaks and valleys of elation and depression especially in the later year when she becomes very difficult to live with. That is one possible explanation for her behavior.

The Whartons’ War

The Civil War Correspondence of General Gabriel C. Wharton & Anne Radford Wharton

Edited by William C. Davis & Sue Heth Bell

get it on amazon

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://lessonsbeyondthestory.com/lessons-learned/what-it-was-like-to-be-a-medieval-soldier