By Michael S. Fulton

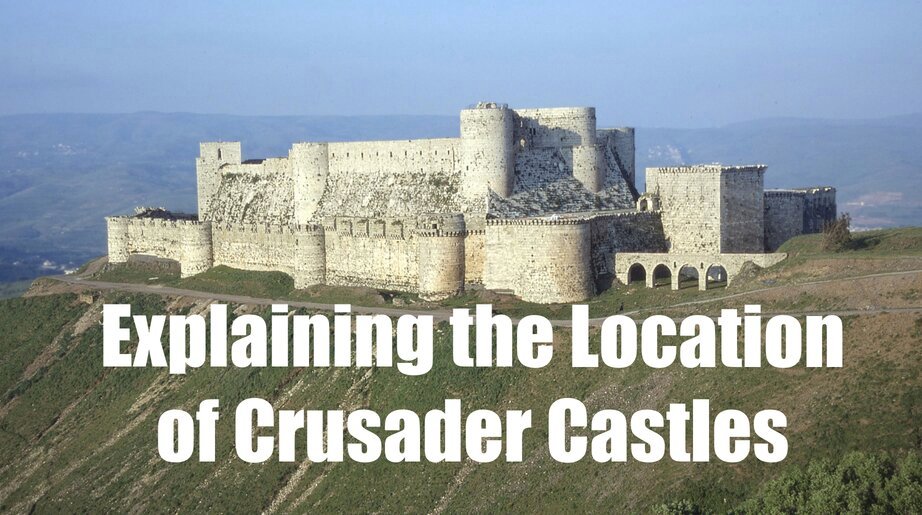

Some of the most impressive achievements of the Crusaders in the Near East were the castles they built. But why did they choose the particular locations they did when it came to constructing these fortresses?

Starting in the late nineteenth century, scholars began proposing reasons to explain why the great crusader castles of the Near East were built where they were. Such theories were put forward by the eminent G. E. Rey, Paul Deschamps, and even a young T. E. Lawrence (known to history as Lawrence of Arabia). The ideas of these men were influenced considerably by the military thinking of their age; they viewed these great castles as markers of frontiers that formed defensible rings around the Frankish principalities of the Levant, functioning in a similar way to the artillery forts built by figures like Vauban.

In reality, the pattern of fortifications that emerged was far less the product of centralized planning than it was the result of a collection of independent and self-interested actions, while the matter of where castles were sited often had little to do with what we might now regard as geopolitical defensive planning. The great castles of the period were far too expensive for a king or prince to implement a defensive strategy that relied on the construction of a number of large strongholds; instead, the pattern of castles that developed across the Levant was the result of a piecemeal process that involved numerous figures. But the question remains: why were the castles built by the Franks constructed where they were? Although there was a unique set of variables responsible for the commissioning of each stronghold, it is possible to discern some general criteria or considerations.

Map of the Crusader States in the 12th century, from textsThe crusades; the story of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, by Thomas Andrew Archer and Charles Lethbridge Kingsford (New York, 1985)InvestmentCastles were expensive to build. Before any figure invested in constructing defences, there were a variety of factors to weigh and circumstances to consider. Foremost, were there sufficient reasons to build a castle in the area considered? If built, could the castle resist a besieging force until relief arrived or the besiegers ran out of supplies? Similarly, how likely was it that the castle would be attacked and how big would be the army sent against it? The stronger a castle was built and defended, the larger the force it could resist and the longer it could hold out, but the more it would cost to construct and maintain.

Although it might be valuable to have a castle deep in enemy territory, or along a contested frontier, it would prove a detriment if that stronghold could not be held – any investment would be to the enemy’s gain instead. Likewise, it was sometimes more advantageous to destroy a castle once captured, even though it had cost the conquerors nothing to build, rather than waste any resources if it was believed the place could not be effectively defended. Baldwin II captured the fortified temple complex at Jerash in 1121, but made no attempt to hold it; Nur al-Din captured Chastel Neuf in 1167, but set it on fire rather than attempt to maintain control of the Frankish castle.

In the thirteenth century, with Frankish power only a shadow of what it had been, the real threat to the Muslims of the region was not the small coastal principalities but instead the ever-present threat of a crusade and the sudden arrival of thousands of European fighters. This led some Muslim rulers to destroy many of the castles that were captured from the Franks, lest they be retaken during a crusade and turned over to the local population of Franks to hold once the crusaders returned to Europe. Large-scale slighting campaigns, directed against strongholds that might be reoccupied by crusaders, were carried out by Saladin, during the Third Crusade, al-Mu’azzam ‘Isa, Saladin’s nephew, during the Fifth Crusade, and by the Mamluk sultan Baybars, who adopted this strategy as a general policy.

Kerak, a castle now in Jordan – photo by evilmoz / FlickrLandscapeIf it was judged profitable, or worthwhile, to build a castle in a certain region, a specific place had to be chosen as the site for the future stronghold. In some instances, a site might offer such obvious advantages that its fortification would be judged worthwhile even if control over the surrounding region offered only modest incentives. In others, what might initially appear to be a valuable or strategically important region would be left relatively devoid of fortifications. For example, the Golan (Sawad), the high ground east of the Sea of Galilee and northernmost portion of the Jordan River, was virtually unfortified, even though Frankish and Damascene armies regularly passed through this area when invading the territory of the other party. This was an exposed and fairly flat region, which offered relatively few naturally defensible sites.

When an initial attempt by the Franks to build a castle here in 1105 failed, construction was interrupted by the arrival of an army from Damascus, it was judged more advantageous to both sides to simply share the revenues of this district. A number of treaties were subsequently concluded through the first half of the twelfth century, which stipulated that the land was to be held jointly by the Frankish ruler of Jerusalem and his counterpart in Damascus.

When designing a castle, topography was an important consideration. Inland castles were often sited on hills or ridges, making use of the topography to add to the defensibility of one or more sides, allowing construction efforts and the allocation of defensive manpower to be concentrated along the most approachable front(s). Some strongholds were built on ends of spurs, leaving only one easily approachable front, which was often secured with a ditch. Among the castles built in such positions can be included Crac des Chevaliers and ‘Akkar in the county of Tripoli; Saone and Shughr-Bakas in the principality of Antioch, and Montfort in the kingdom of Jerusalem. At either end of the Frankish domains, Kerak and Margat, with their adjoining towns, crowned plateaus surrounded by valleys, while Montreal and Harim were built atop steep conical hills. The impressive strongholds of Belvoir and Beaufort were built against steep drops to the east.

The sea castle at Sidon – photo by Pepe Pont / FlickrAlong the coast, water was used in a similar way. The castles (or citadels) of ‘Atlit, Caesarea and Nephin projected into the Mediterranean and were protected by the sea on three sides. Even more extreme, and inaccessible, the sea castles of Sidon and Maraclea were both built on shallows more than 100m offshore. Any castle, citadel or even town built against the sea enjoyed the protection of the water on at least one side.

See also: Why the Crusaders Built Castles: Obvious Answer, Right?

Existing ResourcesWhile it is convenient to discuss where crusader castles were built and why, it is worth bearing in mind that such questions of value had often been pondered before the first wave of crusaders arrived in the Levant – most large ‘crusader castles’ actually rest on earlier foundations. Almost all of the castles in the Syrian coastal mountains were initially established by the Byzantines or Muslim rulers. Only later were these castles occupied by the Franks, becoming parts of the principality of Antioch and County of Tripoli. The notorious Crac des Chevaliers began as the Kurdish castle of Hisn al-Akrad; two subsequent building campaigns, undertaken by the Franks in the late twelfth century and early thirteenth, have since obscured any outward trace of the original structure. The process of development at Crac continued under the Mamluks, who captured the castle in 1271 and further enhanced its defences.

A view of Crac des Chevaliers – photo by peuplier / Wikimedia CommonsSimilar patterns can be seen elsewhere. At Belvoir, recent excavations have revealed traces of an earlier structure that had occupied the site before the Hospitallers built their great castle starting about 1168, although these foundations may be of Frankish provenance, dating to an earlier point in the twelfth century. Similarly, there is textual evidence to suggest that Beaufort was fortified to some extent before the site was acquired by the Franks, though no structures have yet been dated to the period before the castle passed out of Muslim hands in the first half of the twelfth century. Earlier structures probably also rest below many other great castles, such as Montreal, Kerak, and Safed – it is up to archaeologists to confirm or refute this.

Even if a site did not already have an existing stronghold, the presence of buildings was in itself an advantage. Some earlier structures were enhanced and fortified: Muslim builders converted the Roman theatres at Caesarea and Bosra into strongholds, while Frankish masons did the same at Sidon. Elsewhere, where standing architecture was not incorporated into a new castle, the presence of previous building work often provided a plentiful supply of cut stone. The ability to reuse this masonry saved time and reduced construction costs. For this reason, it is not uncommon to find smaller Frankish strongholds positioned in the middle of the remains of a larger classical town or city. For example, Bethgibelin was built on the site of ancient Eleutheropolis, and Bethsan was built among the ruins of the city of Scythopolis, rather than upon the ancient tell where the classical citadel had been located.

An often overlooked element is the presence of a supporting population. Some kind of a local community was essential to provide a castle garrison with basic services, skills, manpower, and usually a source of tax revenue. It was typically easier to make use of an existing population, though some castles appear to have become the nuclei of subsequent settlement. For example, the community around Bethgibelin grew considerably following the capture of the nearby city of Ascalon, taken from the Fatimids in 1153, from which point the region became much safer for Christian farmers. It is noticeable that these supporting communities were rarely fortified. Kerak and Margat are perhaps the best examples of inland Frankish castles with adjacent walled towns, though both settlements appear to have been occupied before the Franks arrived in the region and constructed the castles that now dominate the adjoining towns. Large internal cities, such as Jerusalem and Antioch, often boasted citadels, the foundations of which typically predate the arrival of the Franks.

Along the coast, most large castles benefitted from an adjoining town. It can be confusing whether these should be classified as ‘castles’ or ‘citadels’, though this is ultimately just a matter of semantics. Whereas some larger cities already had citadels, which the Franks developed, it seems new castles were built at sites such as Darum, ‘Atlit and Arsur. One of the clear differences between these coastal communities and those of the interior is the ethnic composition of their populations. The inhabitants of many coastal communities hailed from European backgrounds, while the interior communities that most castles relied upon were probably composed mostly of local eastern Christians.

There were a variety of reasons why the Franks built their castles where they did. The founding of each castle was the result of careful analyses of value, evaluations of the local landscape, and assessments of local resources – each stronghold was ultimately the product of a unique set of motives and considerations. Their position was not, as was believed a century ago, the result of a strategy that sought to surround the Frankish principalities with a ring of defences.

Michael S. Fulton is an Assistant Professor at the University of Western Ontario and an Instructor of medieval history at Wilfrid Laurier University. His books include Artillery in the Era of the Crusades, Siege Warfare during the Crusades, and Contest for Egypt.

Top Image: Photo by Gruppo Archeologico Romano / Wikimedia Commons

Did you miss our previous article...

https://lessonsbeyondthestory.com/world-wars/elite-vikings-wore-beaver-furs-study-finds