By Michael S. Fulton

Building a castle was an expensive process. Yet the crusaders built many fortifications in the lands they conquered. They had many reasons to do so beyond just defending a piece of territory.

Castles are iconic symbols of defensive architecture. At its essence, a castle was a small patch of fortified land, a safe place for the garrison who defended it – even if the surrounding countryside were overrun, this remained an island of resistance. Despite this fundamentally defensive function, most castles commissioned by the Franks (Crusaders) in the Levant were built with far more aggressive ambitions; castles were more than just bases of passive resistance, they could be tools of expansion. This can be seen clearly in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the southernmost of the four Frankish principalities established in the aftermath of the First Crusade (1096–1099), and the one with perhaps the lowest concentration of pre-existing rural castles when the Franks arrived.

More often than not, it was the desire of a king, military order, or lord to subject a region to his authority and administration, to impose more direct control over a region, or to more obviously expand his territory or zone of influence at the expense of a neighbour, or a combination of these factors, that led to the building of castles in this region. When considering the offensive nature of strongholds, it is perhaps worth considering that castles were more often built by powers on the rise, rather than those in decline.

The Crusader States around 1140 – The Historical Atlas, by William R. Shepherd, 1911.Reasons of AdministrationIt was considerations of administration that led to the construction of most Frankish fortifications. Rather than monumental fortresses, the majority of rural strongholds built by the Franks in the twelfth century were instead modest structures, often little more than a tower.

Denys Pringle’s comprehensive survey of surviving secular buildings constructed by the Franks in Palestine reveals how many of these structures were built, though this represents only a portion of the original number. Studies with a smaller regional focus suggest there was probably a similar distribution of such sites elsewhere in the Frankish Levant. Although outwardly unimpressive, some of these modest towers would grow into more extensive fortified complexes, often surrounded with an outer wall, while some would evolve into much larger castles. The earliest phases of Toron, Beaufort, and even Montfort appear to have been a single stout tower, comparable to a European keep.

So many of these towers were built because they fulfilled the basic criteria of lordship. Each was a symbolic seat of power, a defensible place of refuge for the local ruler and his followers, and a safe place where the ruler could store the regional surplus and other forms of wealth. As minor lords did not have the resources to resist a hostile army, these administrative towers only needed to be strong enough to protect those people and things within from bandits and small raids, and perhaps deter potential unrest from among the local population.

View from the top of Beaufort Castle – photo by Julien Harneis / Wikimedia CommonsReasons of ProtectionFollowing the success of the First Crusade and the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the appeal of Palestine as a destination for Catholic pilgrims increased. Internally, however, the early kings and their lords still struggled to impose their authority and eliminate what might be considered bandits, who prayed on travelling merchants and pilgrims.

It was this threat that led to the foundation of the Templars, a brotherhood of knights committed to protecting pilgrims while they visited the holy places of the Levant – the group subsequently received papal support, turning it into a monastic order with a military mandate. Visiting pilgrims from Europe brought prestige as well as wealth to the kingdom of Jerusalem, encouraging efforts to protect these penitential visitors.

This led to the construction of a number of small strongholds along popular pilgrim routes, such as the road from the port of Jaffa to Jerusalem, and that from Jerusalem down to Jericho and the Jordan River. Due to their original mandate, and increasing wealth, many of these small strongholds came into the hands of the Templars.

The castle of Toron in Lebanon – Wikimedia CommonsReasons of ExpansionWhile certain castles were built foremost to facilitate administrative efforts, and some to increase security, the construction of others was driven by more obvious expansionist motives. The castle of Toron, for example, was built in the first decade of the twelfth century by Hugh of St Omer, Prince of Galilee. The castle’s position, at the northern extreme of the Galilee, about equidistance between the Jordan River to the east and the coast to the west, suggests it was built to secure Hugh’s claim to a vast northern region.

The principality of Galilee was initially a huge lordship and one of the first recognized in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, having been established by Tancred, a prominent veteran of the First Crusade. Tancred had captured Tiberius, on the Sea of Galilee, as well as Haifa, on the Mediterranean coast, south of Acre; with Hugh’s construction of Toron, the lordship stretched all the way up to the Litani River, in modern Lebanon.

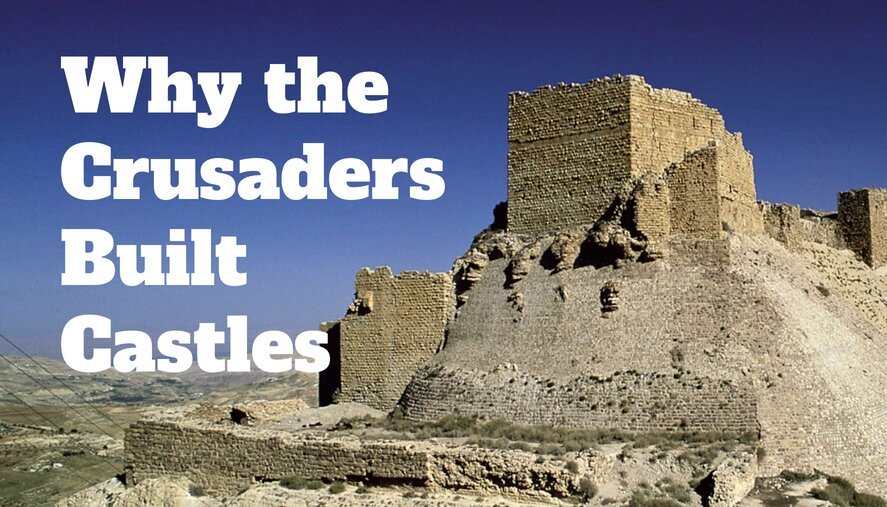

At the opposite end of the kingdom, Frankish authority was extended southward by the monarchy. Baldwin I (r. 1100–1118) led a number of campaigns into southern Transjordan; in 1115, he commissioned the castle of Montreal, on the east side of the Great Rift, between the south end of the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba, the northeastern extension of the Red Sea. It was from this point that Transjordan was effectively claimed and an attempt was made to administer it. The region was initially retained by the monarchy, but was subsequently turned into the lordship of Transjordan. In 1142, the lord at that time, Pagan the Butler, moved the lordship’s seat of power from Montreal to the newly built castle of Kerak. Situated east of the southern end of the Dead Sea, Kerak increased the influence of the lords of Transjordan in the region due east of the Dead Sea.

VIDEO

Castles could be built to claim lands or impose effective rule over a region, but so too could they be constructed as part of an effort to decrease the influence of a neighbouring power. The historian and later archbishop of Tyre, William of Tyre (d. c. 1185), asserts that Toron was constructed as a hostile action against the city of Tyre, 20 kilometres to the west and still in Muslim hands at the time. In 1117, two years after the founding of Montreal, Baldwin I increased pressure against Tyre by commissioning the castle of Scandelion, 14 kilometres to the south of the city.

Tyre was eventually captured in 1124, leaving Ascalon the only remaining Muslim foothold along the Palestinian coast. Against this final outpost of opposition, we can see an even more clear use of castles to effectively blockade a hostile city. During the reign of Fulk (r. 1131–1143), the castles of Bethgibelin, Ibelin, and Blanchegarde were built about 20 kilometres from Ascalon along main roads leading away from the city. It was hoped that the garrisons of these castles could intercept raids launched from Ascalon into southern Palestine, while reciprocal raids could be conducted against the environs of the city. Ascalon was finally captured in 1153, following an extended siege.

In 1178, Baldwin IV (r. 1174–1185) commissioned a new castle at a crossing over the Jordan north of the Sea of Galilee, known popularly as Jacob’s Ford. By this point in time, the Kingdom of Jerusalem was coming under increasing pressure. Saladin, who had become vizier of Cairo in 1169, and then sole ruler of Egypt when he dissolved the Fatimid caliphate in 1171, had assumed power in Damascus following the death of Nur al-Din in 1174. This left the kingdom of Jerusalem surrounded by a single powerful opponent. With this in mind, it has typically been assumed that the castle at Jacob’s Ford was built to prevent an invasion of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from the direction of Damascus.

Ruins of Chastel Neuf – Wikimedia CommonsIn reality, the garrison of the new castle would have been able to do little to impede the progress of a large army. It might also be noted that Saladin typically preferred to use the main crossing south of the Sea of Galilee when invading Palestine, rather than Jacob’s Ford. The castle, which was to be given to the Templars once construction was complete, was instead an effort to expand the kingdom’s influence along this frontier. While the Templar garrison might be able to intercept raids into the kingdom, something they might otherwise have been able to do from Safed, a major stronghold of the order 13 kilometres to the southwest, Baldwin probably hoped the castle at Jacob’s Ford would have a more aggressive function. Placing a garrison of Templars at a natural crossing over the Jordan would facilitate raids into the Golan and towards Damascus. It was also around this time that rebuilding efforts were carried out by Humphrey of Toron, the constable of the kingdom, at Chastel Neuf, 25 kilometres north of Jacob’s Ford and 6 kilometres to the west of the Jordan, opposite the Muslim-held town of Banyas on the east side of the river.

The thirteenth century and Crusader castlesSaladin’s victory over Frankish forces at the Battle of Hattin in July 1187 had a dramatic effect on the balance of power in the Near East. The decimation of the Frankish army meant there was no relief force available to offer support once the towns and castles of the kingdom were besieged, leading them to fall one by one. The Kingdom of Jerusalem was reduced to little more than Tyre by 1189, but the Frankish presence in Palestine was saved by the arrival of the Third Crusade. Although the crusade failed to return Jerusalem to Frankish control, it secured a strip of land along the coast.

Most castle building over the following century was undertaken by the military orders. Major construction projects often corresponded with the arrival of large groups of crusaders, taking advantage of otherwise idol forces – the Templars built ‘Atlit during the Fifth Crusade, and the Teutonic Knights began work on Montfort during the Sixth Crusade. So involved did European crusaders become in construction efforts that James of Vitry, the bishop of Acre from 1216, came to evaluate the success of a crusade based on its ability to besiege an enemy stronghold or to develop existing Frankish fortifications.

VIDEO

Following the collapse of the Seventh Crusade in Egypt, which resulted in the brief captivity of King Louis IX of France (r. 1226–1270), the French ruler returned to Palestine and spent a few years strengthening the defences of the coastal towns. A large portion of northern Palestine had returned to the Kingdom of Jerusalem through negotiations around 1240, but much of this land would end up in the hands of the military orders, as few secular lords could now afford the costs of maintaining and defending large strongholds, particularly those located inland from the coast.

Arsur, as well as Beaufort and the new sea castle at Sidon, were among the last castles to remain in secular hands, but 1260 proved to be a breaking point. The Mongols’ sudden invasion of Syria that year led to the conquest of most territory controlled by later generations of Saladin’s family (the Ayyubids). Mongol rule in Palestine was brief, and the Franks were left alone for the most part. Meanwhile, the Mamluks had taken control of Egypt during Louis IX’s brief imprisonment, following his failed campaign against Cairo. It was the Mamluks who would push the Mongols out of Syria. In September 1260, they defeated a Mongol army at Ayn Jalut, allowing them to extend their authority over the lands that the Mongols had only months earlier conquered from the Ayyubids. This left the Franks once more surrounded by a single powerful neighbour.

In the face of such a dominant opponent, the military orders were the only ones capable of financing the defence of Frankish castles. Julian of Sidon sold Beaufort and Sidon to the Templars in 1260, while Arsur passed to the Hospitallers, but even the military orders were no match for the resources of the Mamluks. Testament to the power imbalance, no Frankish castle was able to hold out against the Mamluks once a siege had been initiated; one by one they fell. Following the Mamluks’ capture of the city of Acre in 1291, the Templars simply evacuated their remaining strongholds along the coast, including ‘Atlit and the sea castle at Sidon; Arsur had already been lost by the Hospitallers back in 1265.

Rather than passive defensive structures, Frankish castles were often built for more aggressive reasons. Those built in the twelfth century were often commissioned to facilitate the administration of a region, to more actively police or pacify an area or route, or actively extend a zone of influence, either bringing Frankish rule over a region or applying pressure along an active frontier.

Things had changed by the start of the thirteenth century, a result of the consequences of the Battle of Hattin. Although a couple of new castles were built during the early thirteenth century, these were fairly unique and corresponded with large influxes of crusaders from Europe. For the most part, fortification efforts dating to the thirteenth century were confined to strengthening or rebuilding existing defences, particularly those along the coast. The high point of Frankish influence had long passed and the rise to power of the Mamluks brought about the beginning of the end of Frankish rule in the Levant.

Michael S. Fulton is an Assistant Professor at the University of Western Ontario and an Instructor of medieval history at Wilfrid Laurier University. His books include Artillery in the Era of the Crusades, Siege Warfare during the Crusades, and Contest for Egypt.

Top Image: Kerak Castle – photo by JoTB / Wikimedia Commons